Interstitial Lung Diseases

Noah Greenspan, PT, DPT, CCS, EMT-B

This chapter is based upon Ultimate Pulmonary Wellness Webinar 18: “Interstitial Lung Diseases” and “Pulmonary Fibrosis and ILD’s: Early Diagnosis and Best Treatments” both with my friend, Robert Kaner, MD; the person who I consider to be one of, if not the tippy-top super guru in Pulmonary Fibrosis (PF), Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), and other Interstitial Lung Diseases (ILD’s).

The subject of Interstitial Lung Diseases (ILD’s) is an extremely complex topic, often even for clinicians, even for physicians, and even for many pulmonary specialists. So, it is no surprise that it is equally if not more difficult for patients and other laypeople.

When it comes to ILD’s, there is a lot of misunderstanding, misinformation, and confusion out there; so much so, that before we even get into the material, I want to highlight three key points right here from the get-go, because failing to appreciate these concepts can literally mean the difference between life and death.

If you take nothing else away from or don’t understand anything else in this chapter, please understand the following three points:

- Early diagnosis and treatment are critical; especially since some of the ILD’s are noted to have a 3-5-year life expectancy from time of onset, although please don’t get hung up on those specific numbers since one, there is variability in these numbers and two, new treatments are being worked on all the time.

- Getting a definitive diagnosis is critical to your care. One of the reasons for this is that some of the treatments used to treat some ILD’s have not only been proven ineffective; but they can be harmful in the case of other ILD’s, meaning that they can make the disease worse by speeding up its progression.

- Having the right team, especially, a pulmonologist who specializes in ILD’s is also critical. ILD’s are serious and cannot afford to be handled by anything less than an expert. I would say “as serious as cancer”, but in many cases, ILD can be more serious in some cases, so only the best and the brightest will do.

If you do not have access to physicians and other health care professionals that specialize in ILD’s then you need to find one, even if it means travelling to an academic medical center or Center of Excellence in another location. In doing so, you can be properly diagnosed and started on the right treatment regimen. Then, after getting a definitive diagnosis and initial treatment plan, you can be managed along with your local pulmonologist. Again, this can literally be the difference between life and death.

Please understand that I am not telling you these things to scare the bejesus out of you. Chances are, that’s already been done. I am telling you these things to impress upon you the fact that ILD is nothing to play with, nothing to sleep on, and not something to dabble with. You cannot afford not to take this seriously. And if you choose to stop reading here, “get thee to an ILD specialist, go.” -William Shakespeare (partially)

When people talk about obstructive lung diseases like Asthma, Emphysema, or Chronic Bronchitis, which are diseases that affect the airways, most people have at least a general idea of what we’re talking about. But…when you say the words “interstitial lung disease” or “ILD,” people generally have no idea what you’re talking about (again, including many clinicians). So, in the interest of getting us off on the right foot, let’s talk about what ILD’s are, what they aren’t; and why they are so difficult to diagnose and treat.

To be clear, ILD is not one specific disease or diagnosis. Rather, ILD’s are a large group of disorders; or more specifically, a category or classification of diseases, that are grouped together because they have similar clinical, radiographic (X-ray or CT scan), and pathological mechanisms.

Anatomy and Physiology

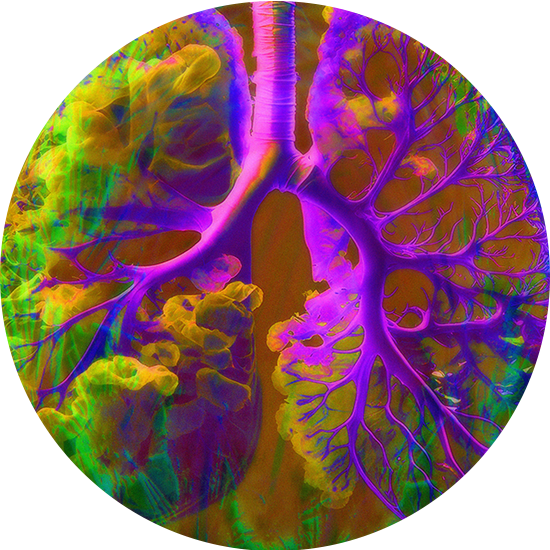

Interstitial lung diseases occur in the alveoli, or alveolar spaces, where gas exchange occurs. Deep within this gas-exchanging part of the lungs, there is an interface between the capillaries, where red blood cells take on oxygen from outside to be used by the body and release carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. The alveolus is surrounded by a very thin structure, called the alveolar wall, which contains epithelial cells that line the air space; and pulmonary capillaries that are only wide enough to accommodate one red blood cell at a time. There is also a connective tissue “scaffolding” that holds that structure together. Interstitial lung diseases are centered on those alveolar walls and the structures that hold the gas exchanging part of the lung together.

Often, people will compare the alveoli to a bunch of grapes. So, if you think of a cluster of alveoli as a bunch of grapes, the alveolar wall would be analogous to the skin of the grape, and that’s what gives it its tensile strength and the ability to maintain its structure. So, the simple explanation is that when you have an interstitial lung disease, the skin of the grape gets thicker, and you end up with smaller grapes with less air in each grape.

But it turns out that the physiology is a little bit more complicated. In a normal lung, you have this very thin membrane that allows oxygen to go from the airspace of the lung into the pulmonary capillary. In a normal lung, the distance that the oxygen must travel to cross that membrane is very short. In the case of ILD, this membrane gets thicker and the distance for diffusion is longer, so the process is going to be less efficient, but it turns out to be even more complex than that. I told you it’s complex!

Think of your pulmonary circulation as a series of parallel pipes. Your entire cardiac output, i.e., the volume of blood pumped by your heart, must travel through these pipes, aka the pulmonary circulation and when we exercise, this cardiac output increases dramatically. In a person with normal, healthy lungs, there is enough capacity in these pipes to allow for this increased cardiac output to travel through the pulmonary circulation effectively.

However, when you have a progressive interstitial lung disease, there’s inflammation and scarring in the gas exchanging part of the lung, and over time, you lose more and more of those pipes. In this situation, the only way you can maintain cardiac output is for the velocity of the red cells to increase, so they start speeding through the remaining pulmonary capillaries faster and faster.

Again, in a person with normal, healthy lungs, the red blood cell is in the pulmonary capillary for about a quarter of a second, and by the time it goes from the beginning of the capillary to the end, it’s completely saturated with oxygen. However, if you lose enough of your pulmonary circulation, the red blood cells may have to go so fast during either exercise or activity, that they are unable to become fully saturated with oxygen by the time they get to the end. This is known as exercise-induced oxygen desaturation, and the more capillaries you lose, the worse it gets, as interstitial lung disease progresses.

Therefore, in people that have interstitial lung disease, their oxygen saturation at rest may be perfectly normal or near normal, but when they exercise, their oxygen saturation drops, sometimes very dramatically and that’s why you may need large amounts of supplemental oxygen when you exercise to compensate for that impaired physiology.

Getting the Right Diagnosis

One experience that we hear from people repeatedly is that they’ve seen “X number of doctors,” or they’ve been short of breath “for X number of years,” and somehow, they still don’t get diagnosed with IPF or interstitial lung disease. It’s actually very common that there’s a lag, sometimes a long lag, between the time people first develop symptoms to getting to a diagnosis of interstitial lung disease, and there are several reasons for that. As you read in the introductions, when people initially develop exertional symptoms, they often chalk them up to being older or deconditioned or maybe having a heart problem or something else altogether, and often, their primary care physician may view it in much the same way, so they may go through an extensive cardiac workup before anyone even considers checking the lungs.

Another reason is that up until very recently, at least for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, there weren’t any pharmacological treatments available for IPF, so some physicians seem to have taken the position of “well, there’s nothing I can do about the disease anyway, so what’s the point of looking for it?” Well, now there are several things we can do, so there definitely is a point in looking for it, and since we know that early diagnosis and treatment is crucial, we would encourage anyone who has unexplained respiratory symptoms to have them investigated.

Diagnosing ILD would be much simpler if we knew for sure, what symptoms we’re looking for. We would be able to tell patients, caregivers, and clinicians, “if you see this, this and this, think interstitial lung disease.”

However, part of the complexity in recognizing ILD, is that most of the symptoms are non-specific for interstitial lung disease. In other words, the main symptoms people experience early in interstitial lung disease, such as cough and shortness of breath on exertion can occur with other diseases like asthma or COPD, Congestive Heart Failure, or Pulmonary Hypertension, among others. In fact, there are a whole host of diseases that can cause those exact same symptoms.

So, it’s helpful to have an attentive physician who can try to sort out which category of disease is causing those problems, and that may involve various kinds of testing. These include a careful history, a good physical exam and some basic tests like a chest x-ray and an echocardiogram. When there’s a suspicion of interstitial lung disease, it’s very important to get a CT scan of the chest, and it needs to be done in a very specific way. For suspected ILD, it’s important to have a high-resolution CT scan (HRCT).

A conventional CT scan gives you images of individual slices of lung tissue that are about 5 millimeters in thickness. To properly diagnose interstitial lung disease, a high-resolution CT scan is required, in which the individual slices are about 1.25 millimeters in thickness or thinner.

Another difference is that during a conventional chest CT, all the images are taken during inspiration. However, when ILD is suspected, images are also taken during expiration. Comparing the two helps to identify a phenomenon called air trapping, which occurs in interstitial lung diseases where there is obstruction of the small airways. This typically occurs in conditions like chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, which is a very important category of ILD’s, and you may not be able to make that diagnosis any other way.

Classification

We know that there are a lot of patients who are living in places where they don’t have access to an academic teaching hospital or COE, and they may not even have access to a pulmonary doctor. In fact, we hear from people all the time that say, “I’ve been going to my doctor, and I’ve been telling him (or her or they) I have a cough and I’m short of breath and still no diagnosis.”

Again, interstitial lung disease is confusing to a lot of physicians and it’s even confusing to pulmonary specialists because ILD patients make up a small minority of the total number of patients that the average pulmonologist would see, and it’s a very confusing area of medicine, both for diagnosis and treatment. And again, since the most expertise in both diagnosis and treatment of interstitial lung disease is typically concentrated in academic medical centers, for people who have those symptoms, and don’t have a definitive diagnosis yet, it might be worth their while to make the trip to at least get the right diagnosis, and then they can be put on the right path to follow up back at home with their own doctors.

ILD’s can be divided into two broad categories:

- ILD’s with Known Causes

- ILD’s with Unknown Causes (Idiopathic)

ILD’s with Known Causes include:

- Occupational Lung Disease

- Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

- Autoimmune and Connective Tissue Disorders

- Pneumonia and Other Infections

- Drugs/Medications that cause Pulmonary Toxicity

- Other Known Causes

Occupational Lung Diseases

Occupational lung diseases are caused by exposures to toxic, inorganic dust that people breathe in, usually while they’re working, such as asbestos, silica, coal, among others. These include conditions like Asbestosis and Coal Worker’s Pneumoconiosis (Black Lung Disease). If someone is diagnosed with Occupational Lung Disease, the first order of business is that they discontinue that exposure as difficult as that may be for many.

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis is caused by breathing in organic dust or antigens such as mold, fungal spores, or bird antigens, for people who keep birds as pets. A lot of times people with HP may not even be aware that there’s mold in their home. As an example, maybe they had a flood years ago and the water was cleaned up, but they didn’t realize that there was mold growing behind the drywall or in their basement.

For people that are in a very early stage of HP where the predominant pathology in their lungs is inflammation, they can expect to see a big improvement in their lung disease once the trigger is removed. On the other hand, if they already have advanced lung disease where there’s already a lot of scar tissue (fibrosis) involved, their symptoms and lung function might stabilize, but it might not improve substantially. Again, yet another case for early diagnosis and treatment.

Autoimmune and Connective Tissue Disorders as a cause of ILD

Another big category of diseases is those that are associated with systemic connective tissue disorders. Examples of common CTD’s include Rheumatoid Arthritis, Lupus, Scleroderma, Sjogren’s Syndrome, Dermatomyositis, Polymyositis, Anti-Synthetase Syndrome, Rheumatoid Arthritis, and others.

Pneumonia as a cause of ILD

In some cases, ILD can be caused by severe cases of bacterial, viral, or fungal infections.

Medications as a cause of ILD

Some medications can cause pulmonary toxicity leading to ILD. The most common ones include bleomycin, which is used for chemotherapy and amiodarone, which is used for a variety of cardiac conditions including Atrial Fibrillation.

ILD’s with Unknown Causes include:

- Non-Specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP)

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF)

- Other Unknown Causes

Non-Specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP)

The other broad category is idiopathic interstitial lung diseases, in which the cause is completely unknown. In this case, they must be correctly classified. One classification is called non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), which is a completely misleading term. For one, there are specific criteria for diagnosing it, and it’s not an infection. It’s an inflammatory disease.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

The other classification is Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), the most common interstitial lung disease of unknown cause. IPF is diagnosis of both inclusion and exclusion, meaning first, all other cause must be ruled out and then the inclusive part is to have definitive evidence of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern in the lung.

In both NSIP and IPF, a surgical lung biopsy is often the only way to make a definitive diagnosis and since there are major differences between NSIP and IPF with respect to their clinical characteristics, prognosis, and treatment, it’s extremely important.

Order Your Book Now!

Purchase Your Signed Copy Today!

- Within the United States: $27.50 including Postage and Handling!

- Outside of the US: $52.00 including Postage and Handling! (Sorry. We know that is more than the cost of the book but we cannot ship for less.)

Subscribe To Our Newsletter For Upcoming Offers

- Be the first to know about new webinars, exclusive offers, and podcasts.